Sunny Right's "The Girl On Horseback"

Going to Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region

During the Cultural Revolution 1966-1976, the Chinese Central Government required our group of young people to go to the mountains and countryside, to receive re-education from poor and lower-middle class farmers.

My mother sold the only desk in the house and one of my favourite skirts. She collected a small amount of money and gave it to me. She gave me a cotton quilt and some clothes. I wore the lambskin coat and bulky clothes that my eldest sister gave me. Wearing a wool padded top, cotton wool padded pants and a pair of cotton wool padded shoes, carrying a dark red, carton paper suitcase which had been left behind by my father a long time ago, I left my home in a large city and set off on the road to Inner Mongolia.

Inner Mongolia is an autonomous region of China. The Inner Mongolian people (referred to as Mongolians) are also one of the 56 ethnic minorities in China.

On the first day, I travelled more than 10 hours by train. I was not in the mood to see the scenery along the way, listening to the roar of the train and the rattling sound of the rolling wheels, which seemed to say that the road is long, long. Looking at the white smoke coming out of the train and the darkening sky, I was feeling confused and gloomy at that time. After arriving, I stayed in a small B&B near the station. The owner added a few dark coals to the fireplace, the coals made a crackling sound without any smoke, and the flames illuminated the dark, old, and simple house which started warming up.

The next day, I took a long-distance bus and continued north to a small town more than 200 kilometres away. The place was where the Han people lived. The roof of the long-distance bus was filled with all kinds of things, boxes, packets of different sizes, dark and dirty. The passengers were talking in Mongolian and Han Languages and carried a strange and unpleasant smell.

On the third day, we continued by long-distance bus. On the bus were a mixture of Mongolian and Chinese people, listening to different languages of Mongolian and Chinese, and wearing different clothes. The Han people wore short jackets and short boots; the Mongolians wore long leather robes, belts and long leather boots. After three days and three nights, finally I arrived at my destination. After arriving at that place, there was no public transportation any more, so I had to take a horse carriage to my destination.

After waiting for two days, a carriage came to purchase goods. I finally had the opportunity to take a carriage. I was very happy to see that the carriage owner was a Han Chinese and could speak my language. He was wearing a thick sheepskin coat, a fur hat, and felt boots. His face was dark and red, with rough, deep wrinkles and his eyes were bright. He readily agreed to give me a lift. I took my suitcase and got on the carriage. His carriage was hitched to four Mongolian white horses, which were not tall but very strong. The tails of the horses were slightly grey. The coachman held a long whip in his hands and sat in front of the carriage. He waved the whip and shouted ‘Ja... ja...’ and the carriage started. I sat on the top of the open carriage and looked up at the distant hillsides and flat grassland which was covered with thick white snow, about half a meter deep. The sunlight reflected dazzling light on the vast white snow. The road across the grassland consisted of three tracks, each going in different directions. Our carriage went along one of the roads. I didn’t know what was waiting for me ahead, and I had a feeling of uneasiness, curiosity, anxiety and expectation.

Before I left home, my sister gave me a lambskin coat to keep me warm. It was a very expensive gift at the time. A lambskin coat can keep out the cold in a big city, but in an open carriage at minus 25 degrees Celsius, it is like a layer of paper. The cold wind soon penetrates, the heat on the body gradually disappears, and the feet begin to feel numb. I told the coachman that it was so cold. He said it would be better if you come down and walk around. The coachman's hat, eyebrows and nose were covered with frost. I had to get down, and rub my hands. I stamped my feet hard on the ground, and my numb feet gradually regained feeling. I had to walk and sit down, repeatedly, until we finally arrived at our destination a few hours later.

One of the girls went back to the big city. She had to take a horse carriage to catch up with the public transport.

When I got off the carriage, my legs were almost completely unsteady, numb and stiff. I was in a hurry to go to the toilet, but my hands were frozen and I couldn't unbutton my pants. I really wanted to soak my frozen hands with warm water, but the local people told me not to use warm water as otherwise my fingers would be rotten. They put my hands in cold water and soaked them. After a while, a layer of ice came out from between my fingers. It was like a layer of ice shell. It was so painful and I was shaking all over. They even wiped my face with ice water. My frostbitten face was thawed, and my hands and face were spared scars. After a while, my hands and feet could finally move easily. This was the most unforgettable, arduous, cold and long road in my life.

From then on, I lived in Inner Mongolia for more than six years. Here I learned how to speak Mongolian, live in a Ger, ride a horse, shoot a gun - it was a completely self-reliant way of life.

The second year after I went there, I was trained as a barefoot doctor.

The barefoot doctors were paramedics trained to provide health care in rural areas during the cultural revolution.

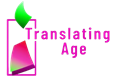

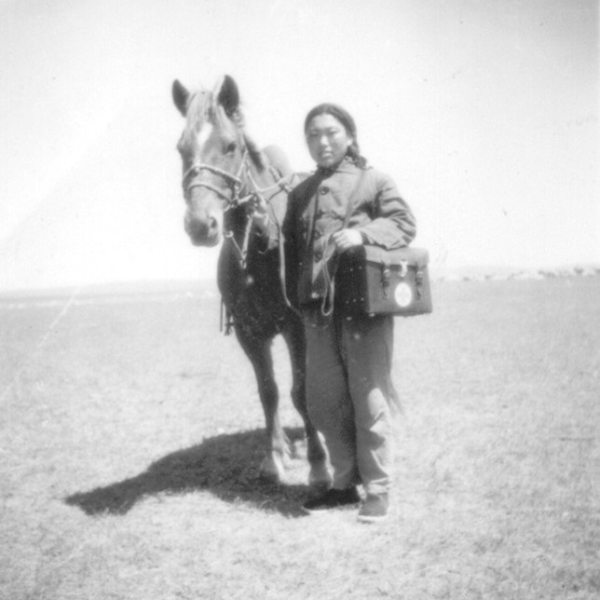

Carrying a small medicine box and riding on a horse, I looked after herdsmen 50 miles around, treating major and minor diseases, offering pre- and post-natal care, delivering babies, and vaccinating children, and I picked medicinal herbs from the mountains twice a year, all as a The Barefoot Doctor. I did whatever I could to save lives, did whatever I could to help them to help relieve the patients' pain.

Although I suffered a lot, after so many years of living there, I developed a deep relationship with the local Mongolians. Since leaving, I often call Inner Mongolia my second hometown.

In 2014, I went back to my second hometown, and people there still remembered my name and what I did for them. The journey this time to Xi Wu only took one day.

Living in a Ger

In the first cold winter 1968, we were 13 in total, aged between 15-21, not prepared for the winter, so we were all assigned to spend the winter in Mongolian Gers which is a type of house where Mongolian herdsmen live.

A Ger (meaning home) is the traditional portable housing structure that forms an essential part of the nomadic lifestyle in Mongolia, allowing herding families to move with their animals as they seek new pastures through the year.

There are four major structures: Mongolian wall brackets, skylights, rafters and doors. Consisting of a circular wooden lattice covered with felt and cloth covers, the transitional Ger is easy to put up and transport by a cow drawn cart. The Ger has a central roof wheel, supported by posts, which allows for summer ventilation also for the use of a centre stove necessary both for cooking and warmth during the cold winter months.

[Image source: Photo by Patrick Schneider on Unsplash]

The Ger has a round pointed roof. The top and sides are covered with one to two layers of thick felt and surrounded by wool felt. The top is about 8 feet high. The wall is about 4 feet high. The door is very low and opens to the south. You have to bend down to get in and out. As I always forgot that the door is lower than my own home, I can’t remember how many times I hurt my head. The Ger is divided into three areas. The north is where the owner sleeps and guests sit, the west is where the children or guests sleep or sit, and the east is where the housewife makes tea and cooks. The outside of the Ger I lived in seemed to be whiter and newer than other people's Gers. The floor was covered with two layers of wool felt, which was a little discoloured and had some wear and tear at the corners. You had to sit down on the ground immediately after bending down. Because the height of a Ger does not allow a person to stand, you have to sit down on the ground. There is a round iron stove in the centre with a large black wok on it for making tea and dinner. Next to the stove is a crock for keeping the boiled brick tea. Next to the crock is a wooden vat which is for making cheese. You must cross your legs after sitting down, otherwise your feet will touch the iron stove. We were used to sitting on chairs and stools in the city. We did not know how to cross our legs, after a while, our legs became numb. Wow, it was hard work.

The family I stayed with was an old couple and one daughter. They were very happy to see me and welcomed me to their home for the winter. The husband was originally a lama, but later he returned to secular life, got married, and had his only child (Buddhism is popular in Mongolia and The Mongols call themselves "the religion of Buddha", but they generally call it Lamaism).

In the late 1930s, Mongolian Buddhism was not approved of. Most temples were closed and many lamas returned to secular life.

The father of the family had big eyes and two gold teeth on each side. He often stared at you and when he talked it was very loud as if he was quarrelling with someone. I was very scared at beginning, later I found out he was very nice man, it was just the way he talked. He was wearing a natural sheepskin robe with black trim and gold buckles, with a purple belt. His robe had pushed up and was a big bulge on his chest, the robe only reached to his knees. It was more convenient to look after cattle and ride horses in this way. His wife always had a serious face. She was wearing a dark blue Mongolian robe trimmed with gold and a blue belt. It reached to her ankles. She was wearing cowhide Mongolian boots. Her face was full of wrinkles and had lost a lot of teeth. Her lips were sunken, and she liked holding her jade small-bowled long-tobacco pipe when her hands were free. She was in her 40s and looked like 70s. But she was very capable. She could sew clothes, make tea and cook, collect cow dung (for stove when the cow pats dry out), make cheese and yogurt and butter. She was really good at it. Her cheese was the best of all at the time. The daughter was two years younger than me. She looked very much like her mother; round face, high red cheekbones, rough skin and a burly body and was wearing a Mongolian robe with gold lace and a bright yellow belt, down to her ankles. We got along very well, like sisters, and the old couple often said that I was their daughter.

He looked after more than two hundred cattle. In the summer, when the water and grass were plentiful, the cattle were let out to graze in nearby pastures. After about two weeks, the nearby grasses were all gone, and they need to move away to find fresh pastures. If you were a sheep herder, you had to move once a week, a typical nomadic life. In the winter, they usually stay in one place, with two or three families staying together. They store the grass cut in the summer in the haystacks and feed the old, weak, sick and disabled cows in the winter, and let the strong cows out.

I started life in a Ger with this family. At night, they turned off the stove, pulled the top of the Ger (tent) over and closed out the sky, and lit the oil lamp. The light was very dim. The mother and father slept in the north with their heads to the northwest. Their daughter and I slept in the west with our heads to the north. The man took off his boots and put them over his head, which was also near my head. The smelly boots kept me awake for a long time. Covered with the cotton quilt I brought from Beijing, I fell asleep and woke up in the middle of the night. Without a fire, the Ger was like an ice cellar.

My feet began to feel cold, and gradually my thighs, abdomen and arms all became cold, until there was only heat remaining in my chest, and I couldn't lie down any longer. I thought I was going to be frozen to death. There was a thick layer of ice on top of the quilt from my breath which made me even colder as it touched my face. I hoped the mother would get up soon to light the fire. Finally I heard her get up. She knelt on one knee with the other crossed under her buttocks. The Ger slowly began to warm up. And we all got up too. The wife handed a scoopful of water to her husband, daughter and me, I did not know what this was for? Then I saw them use water to wash their faces and rinse their mouths. No toothpaste, no towels and soap, just dry yourself with your robe. I did exactly as them.

The wife cut the brick tea into fine pieces, put it in the big black pot and boiled it. After the tea turned golden, she poured the tea into the crock, discarded the tea leaves, and put the tea back into the black pot, adding some salt and millet to the brew. Everyone drank tea with a bowl, no cups, mugs or spoons for drinking tea. She shook the teapot and poured tea into the bowls, there was some millet at the bottom of the bowl. I looked at the grains and wondered how I could get them out of the bowl? I watched Ama and his daughter; they cleaned their bowls with their tongues. When you got the bowl cleaned, then the wife would pour another bowl of tea for you. I didn’t know how to use my tongue. I felt embarrassed and my tongue did not seem long enough to reach the bottom of bowl. I often ended up feeling very hungry after drinking tea. Sometimes the wife would give me a piece of biscuit made by herself or a piece of cheese, and sometimes she would also put a little butter in the tea, which was a very special treat.

In the first two photographs you can see the family I stayed with the first year in Inner Mongolia in the 1960s.

The third and fourth photos are of the daughter and father with me when the family came to my home city.

The last photo is me wearing the sheepskin robe with black trim and gold buckles, scarf on like a Mongolish girl.

Militia military training in Inner Mongolia

I looked at the photo of me squatting on the ground and dragging a long rifle to practise aiming, which reminds me of the time of militia military training in Inner Mongolia.

Never having ridden a horse, let alone seen a gun, military training was one of my least favourite things. But at that time, Sino-Soviet relations were very tense, and we had to carry out militia military training to guard against the danger of invasion.

I was issued an old-fashioned rifle that was as high as my shoulders, and it was heavy. Each person was given a bullet bag around his waist, which looked full, and there were only 5 rounds of experimental bullets. There were red spots on the bottom of the bullets, and there was no explosive in them. Others were fake bullets made of paper, just to make up the numbers.

I am not tall and without a gun, I could fly onto a horse back. But it was very difficult to mount a horse with a heavy gun on my back. I held the saddle running on the ground and circled a few times but couldn't get up. It took a lot of effort to get on the horse.

When we arrived at the training ground, the instructor first taught us to aim. He taught us to pull the gun bolt, load the bullet, pull the trigger, and so on. We, a group of 18 or 19-year-olds, were lying on the ground, holding a gun in one hand, doing as the instructor said, aiming the two gunsights on the barrel and trying to line them up with the target. My hands were shaking constantly, I couldn't find my line of sight, and I didn't know how to aim. My eyes gradually blurred, wet. "This is military training, don't be weak," I said to myself. Gradually, my heart calmed down, I wiped away my tears, and continued to practise. After a period of training, I could aim and my hands didn’t shake much anymore, but I was always afraid that the recoil of the gun would hurt my shoulder when I pulled the trigger. Every time I pulled the trigger, I could not help but move my shoulder back. The more I did, the more painful it was. Slowly I learned to hold the butt of the gun against my shoulders as tight as I could before pulling the trigger. This was not easy for me who had never seen a gun, let alone had any military common sense. I didn't understand the classification function of weapons at all, it was really too difficult. But that was just the beginning.

White horse Company

I see white horses standing in a row. Some horses have a little grey hair on their necks or their hooves, but the whole body is white, and the warriors stand beside the horses, carrying different weapons on their backs, rifles and semi-automatic rifles, while the company commander has a pistol. Hearing a soft whistle, the white horses lie down silently. The soldiers use the horses as cover, put their guns on the saddles, and are ready to shoot. Another soft whistle is heard, and one hundred white horses lying on the grass stand up silently, and then the soldiers fly onto the horses and gallop in the direction pointed by the whip in the company commander's hand. They are so quick and look easy and relaxed. I secretly admire them in my heart. Later I learn that the white horse is not easy to find in the snow.

We are about to serve as a militia and equestrian training has begun. There are three kinds of equestrian skills: one is sword fighting, that is, riding on a horse, passing dummies standing on both sides, and swinging the sword left and right to chop at the standing dummies; the more cuts, the better. The second is to shoot from the horse, riding on the horse, putting down the reins of the horse, bringing the heavy gun from the back to the front, and shooting the target while standing on the horse and galloping. The third is trench jumping, riding on a horse and jumping over a ditch about 2.5 meters wide and 1 meter deep.

I quickly passed the sword fighting, and I also passed the shooting from the horse. The most difficult thing is to jump over the ditch. I couldn't jump over it no matter what, I was afraid to fall, afraid of broken bones or even death and my horse seemed to sense my feeling and was also afraid. Whenever I reached the edge of the ditch, my horse stopped. It failed several times. Then the instructor ordered, "If you can't jump over today, you are not allowed to go home." I thought it was terrible news, do I have to spend the night in the wild? There is a danger of being eaten by wolves, and the more I thought I became more frightened. I made up my mind to jump over it, since I couldn't let the wolves eat me. I patted the horse's neck and said: “my dear, we have to jump over!" After I talked to my horse, I clamped the horse's belly, using my riding boots with spurs. The more I clamped him and whipped his rump, the faster he went. We rushed to the ditch with my eyes closed. As soon as we jumped, I broke out in a cold sweat. I thought we couldn’t jump over and I would fall to my death. But when I opened my eyes, ah, we had jumped over. After intense and arduous training, finally I passed all the assessments.

Some of the photos below show me on the horse with Lasso pole, holding the gun on the grassland, and with my horse near the water.

My Shoes

Look at this pair of Chinese hand-made shoes which remind me the journey of my life.

Each period of life or journey from the beginning, can be recognised by the type of footwear worn.

Look at these boots which are very similar to the boots I wore in Inner Mongolia.

In the 1960s I went to Inner Mongolia, I was on horseback nearly all the time, the boots are very important to keep me warm and safe on the horse.

1991 was the second time I left home and this time I went to Europe. These boots were bought in Poland, which are made from sheepskin for the cold winter.

I learned English bit by bit and integrated with the society.

I worked in London and later came to Northern Ireland. At work, I had a lot of meetings and learned to dress up and even had handbag and shoes to match.

My Scottish dancing shoes. I like Scottish music and Scottish Country Dancing.

Ballroom Dancing shoes. I learned Sequence Dancing and enjoyed it very much.

Golf shoes and bowling are very much a part of my retired life.