The Plays: 'The Freedom of the City' (1973)

Premiered

- 20 February 1973 at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin. Concurrently produced at the Royal Court Theatre, London from 27 February 1973.

Published in

- Brian Friel - Collected Plays: Volume Two, The Gallery Press / Faber & Faber (2016).

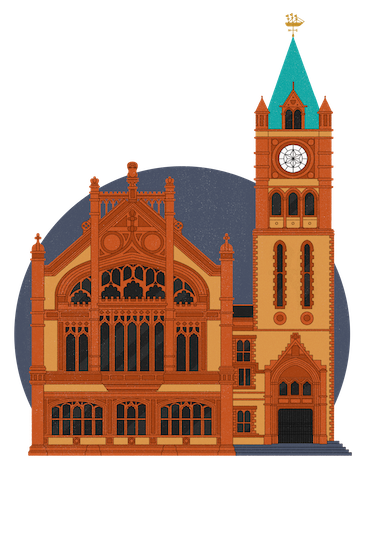

Illustrations by

- Lydia Hughes, commissioned by the Friel Reimagined Project, 2022.

Three people stumble into the wrong place at the wrong time. This is a familiar dramatic scenario, but it’s put to powerful use by Brian Friel in The Freedom of the City, set in Derry in 1970.

The play’s protagonists – Lily, a cleaner and mother of eleven children, Michael, a committed civil rights activist, and Skinner, an enigmatic young man who thrives in the chaos of the moment – find themselves at the symbolic centre of power in the city, the Mayor’s Parlour in the Guildhall. Escaping to safety after a civil rights meeting in the streets outside has been disrupted by army tear gas and rubber bullets, the trio don’t yet realise that their mere presence in this hallowed location in such tense circumstances will cause enough confusion to seal their fates.

Friel pits differing accounts of the day’s events against one another, introducing tension and conflict throughout the play – and not only between the innocent marchers and the authorities who act as though responding to a provocation.

The three protagonists have arrived at this moment bearing quite different perspectives, causing many clashes of opinion during their time together. Skinner seems to enjoy winding up the more serious and thoughtful Michael; Michael in turn cannot make sense of the motives of the other two. Friel also juxtaposes the bleak sense of inevitability in the play with uproarious comic relief in the exchanges between Skinner and the world-weary Lily. Despite being trapped in the same situation at close quarters, they do not share the same outlook on why this has come about, or how best to resolve the situation. For the time being, they make themselves comfortable in the opulent surroundings of the Mayor’s parlour – Skinner especially is happy to roam around, smoking cigars, putting on ceremonial costumes and assuming comedic personas to entertain (or confuse) Lily and Michael.

The action of the play rarely stands still until its final moments.

Tapping into the intense scrutiny around the events of Bloody Sunday (which occurred in 1972 when Friel had already begun writing this ‘civil rights’ play, and which influenced its final form), there are frequent sudden jumps in the action, switching from the Mayor’s Parlour to happenings outside. One moment, there are soldiers crouching at street corners, trying to make sense of what is going on and the orders they are being given; the next, the tribunal judge appears high on the battlements of the city walls, receiving (contradictory) eyewitness testimony and adjudicating on the events of the day in hindsight. We see a TV journalist deliver his reports and witness an army press officer wrongly declare that a ‘band of terrorists’ has taken over the Guildhall. We also hear fragments of the loudhailer speeches at the fateful civil rights march – a sense of solidarity and peaceful protest before a tragic descent into violence.

The fragmented feeling in the play, akin to a breaking news bulletin, would have been only too familiar for audiences at the time. The events of the day begin to become clearer as Friel contextualises them from numerous angles, to reveal how such a perilous situation could have emerged from the simple, instinctive decision to run through a side door for cover. These frequent changes in perspective only deepen the audience’s connection with the three individuals at the centre of the maelstrom. For all the vivid energy of the three in the Mayor’s Parlour, and for all the explanation and excuses that are offered, the audience is aware from the moment the stage lights up that a sad fate is in store for Lily, Michael and Skinner.

Thus, from the outset, the play provokes numerous questions: How was this allowed to happen? How did it spiral out of control? Who was at fault? In the end, Friel grants the tribunal judge the right, and the responsibility, to respond. Yet despite being the last person to speak in the play, his pronouncements are not the final word. His authoritative speech, condemning and cynical, is betrayed by the figures of Lily, Michael and Skinner, who stand lit up at the front of the stage with their hands above their heads, ‘looking straight out’. Their presence in the wrong place at the wrong time will cost them their lives, revealing the deeper questions at stake in Friel’s most overtly political work: Who has the right to walk the streets with safety and dignity? Who can be granted ‘the freedom of the city’, and who is allowed to ask?

A woman addressing the civil rights meeting before it is broken up by water cannon, rubber bullets and CS gas.

Skinner to Lily and Michael in the Mayor's Parlour.

Friel's stage directions at the end of The Freedom of the City.

More on The Freedom of the City

- Roche, Anthony (2011). ‘The Politics of Space: Renegotiating Relationships in Friel’s Plays of the 1970s,’ in Theatre and Politics, pp. 105-129. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Watt, Stephen (2006). ‘Friel and the Northern Ireland “Troubles” Play,’ in Roche, Anthony (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel, pp. 30-40. Cambridge University Press.

About the Illustrator

Lydia Hughes is an Irish illustrator and design based in Westport, Co. Mayo. She graduated with a BA in Visual Communication from Herefordshire College of Arts and practised as a visual designer in the UK, Canada and Ireland before going on to complete an MA in Illustration with the University of Hertfordshire. Her work is characterised by flat, minimal, geometric shapes, reflecting a longstanding love of mid-century aesthetics, traditional printmaking processes and a background in graphic design. She harnesses playful colours and warm textures to deliver simple visual narratives that feel inclusive and friendly yet polished.

-

About the Friel Reimagined Illustration Programme

The Friel Reimagined Project is delighted to work with five talented Irish and Northern Irish illustrators to help introduce Friel's work. Each of them has each chosen one of Friel's plays to interpret in their own illustration style. Their work will appear on the Friel Reimagined website throughout 2022.

Illustrator Play Fuchsia MacAree Philadelphia, Here I Come! Lydia Hughes The Freedom of the City Ashwin Chacko Faith Healer Dermot Flynn Translations Ashling Lindsay Dancing at Lughnasa